What you need to know

‘What couldn’t be said in Taiwan, we said it here [in the U.S.]; what couldn’t be done in Taiwan, we did it here.’

China's soft power has become a major concern for Taiwanese activists in the United States who strive to increase Taiwan’s global visibility. Now, more than ever, they are calling for Taiwanese Americans and expats to fight back against those Chinese actively spreading Beijing’s ideologies.

The Chinese Students and Scholars Association, which has chapters in universities across the U.S., last month condemned one university for inviting the Dalai Lama to speak. A few days later, it accused a Chinese student of “not loving China” because she praised U.S. freedom and liberty in her graduation speech.

Wen Liu (劉文), 30, a doctorate graduate based in New York City, is one of a group of Taiwanese in the U.S. keeping up a long tradition of fighting for freedom and democracy for their home country.

“People are moving around and bringing in politics and power, and we just can’t erase the influence [Chinese] people have here,” she told The News Lens in New York. “A lot of people are also going back to work in China or Taiwan and different parts of Asia, so if we don’t fight for that here in the U.S., it’s going to be even harder to do so in the Asia-Pacific area.”

Taiwanese-Canadian Gloria Hu (胡慧中), another activist in New York, echoes Wen Liu. While Taiwanese identity is strong among some Taiwanese in the U.S., it is not well understood by most Americans.

“And so when somebody says Taiwan, if anyone has any idea of East Asian politics, they will just say, ‘It’s complicated,’” says Hu. “China is very actively spreading their ideals and we need to do what we can to fight back against that.”

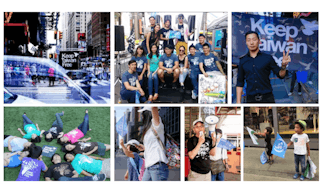

Photo Credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Young Taiwanese activists in the U.S.

Wen Liu moved to the U.S. when she was 16 and has been studying and teaching gender rights and sexuality studies for the past 10 years. The 30-year-old is involved with the Taiwanese activist community in the U.S. and works to bridge minority groups in Taiwan, including LGBTQ and indigenous communities, with the Taiwanese independence movement.

Also passionate about LGBTQ issues, Hu is working to promote a “progressive Christianity” in Taiwan that is up-to-date with LGBTQ and women’s rights. She is also associated with the United Nations Membership for Taiwan – Keep Taiwan Free movement, a coalition advocating for Taiwan's freedom and democracy, co-directed by 26-year-old Taiwanese American Jenny Wang (汪采羿).

“Growing up, my parents always told me that I was Taiwanese, and I never really questioned it,” says Wang. “But then as you grow up, you get all these people who challenge you. They might go, ‘Oh, you’re Taiwanese. Why not just say you’re Chinese?’ And I wanted to understand why there are these issues.”

Since joining the Keep Taiwan Free movement (originally the United Nations for Taiwan Rally, founded in 1993) nearly six years ago, Wang has changed the organization’s approach. Instead of the sole focus being Taiwan’s re-entry into the U.N. — Taiwan lost its membership in 1971— she wants to raise broad international awareness of Taiwan’s current diplomatic status and the risks facing its democratic system.

Though other Taiwanese activists in the U.S. share Wang’s passion, they face two key questions: Why should people care about Taiwan? How do you get them to care?

“Taiwan has a lot of values that are aligned with American values or universal human rights. That’s how you talk about it to people who aren’t Taiwanese; you draw them in with these interesting facts that are really important,” says Wang.

Photo Credit: Chris Nicodemo

Wen Liu agrees with Wang’s approach and says introducing Taiwan to others through "anti-war sentiment" has been effective in her own work.

“Especially the leftists in the U.S., they often think about Taiwan as a much more pro-capitalism place, as opposed to the Maoism in China, so they kind of have this fantasy about China as the next big socialist movement,” she says. “In Taiwan, there is a lot of the leftist energy, but it’s not as recognized. As a Taiwanese, I believe we should really intervene in the leftist discourse.”

Hu adds that in the age of President Donald Trump, young people are even more willing to talk about the democratic institutions they value.

“They think about why democracy matters to them, and why do me and my friends feel unsafe in this country now as a result of what’s happening in the U.S. How can that be applied to Taiwan?”

While their work is different from the more “grassroots” or “frontline” activism in Taiwan, Taiwanese activists in the U.S. believe their calls for international support are effective, especially when catching the attention of the media.

Liu Yen-ting (劉彥廷), 31, arrived in New York City for graduate school in 2012 and has participated in movements such as the 2012 Anti-Media Monopoly Movement, the 2014 Sunflower Movement, and LGBTQ activism. The doctorate student is affiliated with Café Philo in New York City — a series of salons facilitating conversations about Taiwanese social, cultural and political issues.

He says U.S. media coverage on Taiwan-related issues influences discussion around Taiwan. An example is the phone call between then President-elect Donald Trump and Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) late last year. The call was thought to be the first time a president or president-elect of the United States has directly contacted the leader of Taiwan since 1979 when formal diplomatic ties between the United States and China were established. The story was reported around the world and many framed their coverage to make it seem like the Taiwanese were pro-Trump.

“There was a group of us that worked to tell Americans that not all Taiwanese were pro-Trump or Republicans,” says Liu Yen-ting, who refers to a Washington Post op-ed written by Taiwanese activists Chen Wei-ting (陳為廷), Lin Fei-fan (林飛帆) and June Lin (林倢) after the historic phone call.

Where it all started

The movement can be traced back decades.

Dr. Lai Hong-tien (賴宏典), now in his late 70s, arrived in the U.S. in 1967 as a graduate student in Georgia. He then transferred to Buffalo in Upstate New York, where he met a group of Taiwanese students and started discussing political issues in Taiwan — something that was forbidden at the time under the Kuomintang (KMT) Martial Law rule of the island-nation.

“Our generation of overseas Taiwanese students was probably pretty thoroughly brainwashed by the Kuomintang education back in Taiwan. Most of us were good students so we were more conservative and accepted whatever was taught,” says Lai.

The now retired dentist and his friends would talk about “the delusions of the education” they had received, and Lai, along with others, increasingly grew disgusted with the unjust government. After graduating in 1972, Lai started practicing in New York City and was recruited by a friend from graduate school to join The United Formosans in America for Independence (UFA, 全美台灣獨立聯盟) in 1976.

“We mostly held rallies on the streets back then; for example, when the KMT arrested those advocating for democracy in Taiwan. I was part of all these activities,” says Lai. “What couldn’t be said in Taiwan, we said it here [in the U.S.]; what couldn’t be done in Taiwan, we did it here.”

The activists understood a movement like this wasn’t just for a day or two. While it was slow, they did see progress, especially during the Kaohsiung Incident (also known as the Formosa Incident) in 1979. The pro-democracy protests in Kaohsiung, southern Taiwan, resulted in a major crackdown by the KMT and eight of the movement's leaders being imprisoned for years.

Two years before the incident, the Presbyterian Church presented to the international community “A Declaration of Human Rights” on Taiwan’s political situation, urging leaders to “face reality and to take effective measures whereby Taiwan may become a new and independent country.” As a Christian, Lai was deeply moved by these words, and along with his fellow activists, grew anxious after the Kaohsiung Incident. They scrambled to meet with U.S. congressmen and senators, urging them to take action against what was happening in Taiwan.

“I think it’s because all of this built international pressure on the KMT, they had to hold an open trial [of the Kaohsiung Incident leaders],” says Lai. “Before this, these kinds of trials were held behind closed doors."

Photo Credit: Provided by Jenny Wang

In the 1980s and 1990s, activists in the U.S. continued to push for international awareness of Taiwan’s political status and democracy. Organizations, like The Formosan Association for Public Affairs (FAPA), were founded in these decades to increase the country’s global visibility. One of the main events was the annual United Nations for Taiwan Rally, which started in 1993 — 22 years after Taiwan lost its U.N. membership.

According to Lai, there was two main goals: to make the global community learn about the injustices happening in Taiwan and educate the Taiwanese; and, to turn the island-nation into “a new and independent country” in which the people could make decisions and decide their own future.

With the arrival of a younger generation of Taiwanese expats and second generation Taiwanese Americans growing up in the United States, Lai’s generation is now stepping down from the decision-making roles in Taiwan activism in the U.S. and handing over the reins to a new generation of Taiwanese activists.

“I think the minds of the younger generation are cleaner. Our generation had a kind of hatred toward the KMT. There was this idea that Taiwan would never be better if the KMT wasn’t defeated. I wasn’t prosecuted directly, but there was this feeling that we had been deceived,” says Lai. “The younger generation identifies with Taiwan and loves it as their own country. I was especially moved during the Sunflower Movement.”

Bridging the gap

While both generations have similar aims of boosting the global visibility of Taiwan’s independence and democracy movements, the younger generation of Taiwanese activists in the U.S. still strives to reassure the older generation their legacy will be carried on.

“A very important role Taiwanese students have here is to bridge the gap between the Taiwan independence movement of the older generation [with the one today],” says Wen Liu. “There is that anxiety that we’re not doing it the way they want.”

The activist says the older generation did a lot of lobbying for Taiwan’s independence, but now the younger generation is trying to create an alternative vision for Taiwanese independence. Wen Liu believes they shouldn’t stick to the idea of Taiwan having to rely on support from the U.S. because the movement is not just about choosing U.S. supremacy over China.

The older generation is conservative and has focused on how Taiwan’s independence could benefit the U.S, Liu Yen-ting says. They also tend to leave Taiwan civil society out of the discourse.

“The younger generation of Taiwanese cares about how civil society can create a Taiwan identity and how it can affect the global civil society. This is something the older generation talks less with us about,” says Liu Yen-ting.

Discussing topics like international relations and geopolitics can be off-putting for second generation Taiwanese Americans, says Hu. Younger Taiwanese try to humanize issues like democracy in Taiwan to show how they affect the general population.

There is still tension between the generations.

“If the older generation wants us to continue their work, they have to listen to us,” says Wen Liu. “They have to accept we have a different vision, and sometimes they need to learn from us as well. There’s a different way of doing activism now and we’re doing the best we can.”

Photo Credit: Overseas Taiwanese for Democracy

Staying motivated

Still, Taiwanese across the generations continue to collaborate closely. Wang is working with Lai on the Keep Taiwan Free Rally. At Café Philo events activists from the older generation are invited to give talks on their experiences.

“I’m happy to see the younger generation taking over,” says Lai. “Being young has a lot of value.”

He points out there are advantages to doing activism in the internet era and the Taiwanese activists today have better English language skills than their predecessors, making it easier for them to explain issues clearly.

“The younger generation probably has it a tiny bit better than we did because we support their funding whenever we can,” says Lai. “They have fewer concerns. At least I hope so.”

The four young Taiwanese activists are uncertain whether or not they will return to live in Taiwan. They each have their own motivations to continue their activism: doing it for their children; being offended when people misunderstand Taiwan; seeing positive incremental changes; and, sharing the passion with others.

“This movement is passed from one generation to the next — even if they have different ideas and approaches. The goal is to promote Taiwan as a new and independent country,” says Lai. “This dream can’t be realized easily, but I hope it comes true soon.”

Photo Credit: Eric Tsai

Editor: Edward White