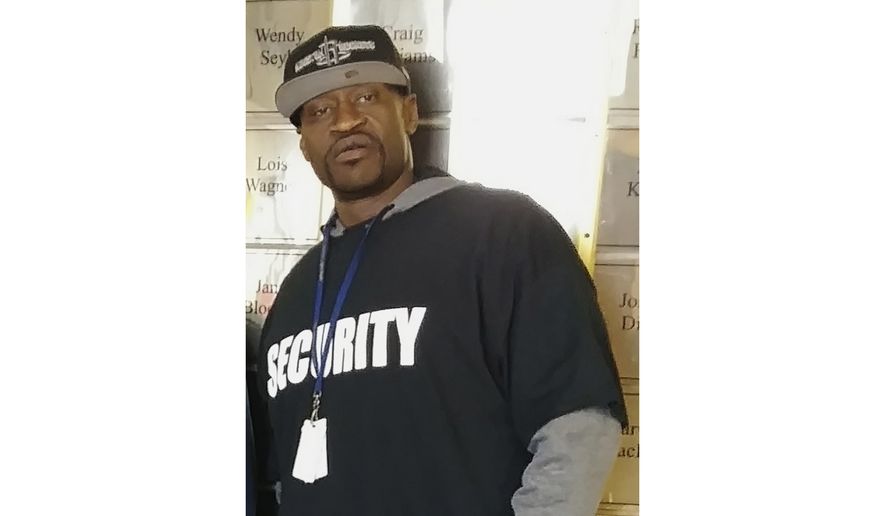

In death, George Perry Floyd Jr. has become a civil rights martyr and a catalyst for social justice. In life, he was a mass of contradictions.

At his best, “Perry” was a beloved family man and standout athlete who rededicated his life to Christ after running afoul of the law, a community leader in Houston’s rough 3rd Ward and doting dad to his precious 6-year-old daughter, Gianna.

At his worst, Mr. Floyd was a drug addict and ex-con who did hard time for a 2007 robbery in which he terrorized a Hispanic woman who was at home with a baby, and absentee parent to his older children, one of whom didn’t recognize him when his photo appeared two weeks ago on television.

Patrick “P.T.” Ngwolo, an elder at the inner-city Christian mission Resurrection Houston, may have put it best when he said Mr. Floyd, who stood somewhere between 6 feet, 4 inches and 6 feet, 7 inches was “larger than life.”

“Mr. Floyd was a person who was what we call in the neighborhood an OG, somebody who had been through the wars, who had made the mistakes and who was able to go back to a generation and say, ‘Hey, guys, this is the way you ought to move, this is how you ought to do it,’” Mr. Ngwolo told Fox News.

He said Floyd used his status as an “OG,” or “original gangster,” to help the church make inroads in the Cuney Homes public housing complex, also known as “the Bricks,” by reaching out to neighbors, participating in basketball tournaments and setting up chairs and tables for services every fifth Sunday.

If not for George Floyd, he said, “my ministry would not exist.”

Mr. Floyd quickly became the face of the social justice struggle when he died May 25 after a Minneapolis police officer knelt for nearly nine minutes on his neck while arresting the 46-year-old for allegedly passing a phony $20 bill.

The Hennepin County medical examiner has ruled his death a homicide, and former Officer Derek Chauvin and three others have been charged.

At a memorial service in Minneapolis, his brother Philonise Floyd said that “everybody loved George.” His cousin Shareeduh Tate called him “this great big giant” who “always made people feel like they were special.”

“When I was trying to make headway in the neighborhood, I needed some allies, somebody who would introduce me to people, would allow the ministry to happen in the neighborhood with relative safety, and who was loved, admired and respected in the community,” said Mr. Ngwolo. “The Bible would call that a person of peace, and I would describe George Floyd as a person of peace.”

Those who knew him 20 years earlier might disagree. In 1997, he was arrested on a charge of possession of less than 1 ounce of cocaine. It was the first of eight arrests on drug and theft charges that culminated in the 2007 robbery of a woman’s home in Harris County, according to records posted by the [U.K.] Daily Mail.

The woman, who was home with a one-year-old girl, “tentatively identified defendant George Floyd” as one of the men who forced his way into her home by pretending to work for the water department, pointed a gun at her abdomen, and forced her into the living room. The men took jewelry and her cellphone before leaving.

Mr. Floyd served five years and was released in 2014. He joined Resurrection Houston and became involved with Roxie Washington, who gave birth to their daughter, Gianna. Three years ago, he moved to Minneapolis in what his aunt Angela Harrelson, who lives there, described to the Los Angeles Times as an effort to “make a fresh start.”

In Minneapolis, he dated Courteney Ross, who has told media outlets that she was his fiancee. He worked at one point as a bouncer at the Conga Latin Bistro.

“Everybody loved Floyd,” Jovanni Thunstrom, his employer at the bistro, told KARE-11. “We all have good memories of him.”

It’s unclear whether Mr. Floyd started using drugs again after leaving Houston, or whether he ever stopped, but his autopsy report said fentanyl and evidence of methamphetamine use were in his system.

Conservative pundit Candace Owens, who is black, posted a video last week in which she criticized activists for lionizing Mr. Floyd. In the black community, she said, “it has become extremely fashionable for us to martyr criminals.”

She emphasized that she was not defending Mr. Chauvin. “Everybody agrees what he did was wrong,” she said, but she criticized those who wanted to “make [Mr. Floyd] the modern Martin Luther King Jr.”

“This is a man that had drugs on him, was using counterfeit bills and was high, and went into a store and the police were subsequently called,” Ms. Owens said.

Confession: #GeorgeFloyd is neither a martyr or a hero. But I hope his family gets justice. https://t.co/Lnxz0usrp5

— Candace Owens (@RealCandaceO) June 3, 2020

Police Federation of Minneapolis President Bob Kroll said in a letter last week that Mr. Floyd had a “violent criminal history.” He said the media “will not air this” and accused politicians of scapegoating officers overwhelmed by the protests and rioting.

Born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1973, Mr. Floyd grew up in a poor but loving family, according to his brothers and relatives, who remembered fondly the man known as “Perry,” “Big Floyd” and “Big George.”

After his parents divorced, his mother, Larcenia “Cissy” Jones Floyd, moved the family to Houston. As a single mother, she was known for preparing enormous meals for her strapping sons and feeding any neighborhood children who were hungry.

The family could not afford a washing machine or dryer — the boys washed their underwear and socks in the sink and dried them in the oven — but George Floyd had a way of making people feel special.

“Guys that were doing drugs, like smokers and homeless people, you couldn’t tell, because when you spoke to George, they felt like they were the president,” Philonise Floyd said at the memorial service. “Because that’s how he makes you feel. He was a powerful, man, he had a way with words, he could always make you jump and go, all of the time.”

“Big George” was a talented football and basketball player at Yates High School and received a scholarship to play at what was then South Florida Community College. He left in 1995 before earning his degree, the Houston Chronicle reported. His first arrest was two years later.

Multiple media outlets have said he had three children, although Ms. Tate said at the memorial service that he had five children and a granddaughter. He apparently lost touch with his children Quincy Mason Floyd and Connie Floyd, who moved to Bryan, Texas, with their mother 15 years ago.

“I didn’t recognize who it was until Mom called and told me,” Quincy Mason Floyd told KBTX-TV. “She said, ‘Do you know who that guy was?’ I said no. She said, ‘That’s your father.’”

Even so, he and his sister said they were pleased by the local protest march against police brutality and in favor of social justice spurred by their father’s death.

“I’m really excited about all this,” said Quincy Floyd. “Everyone is coming out and showing him love. I love this. My heart is really touched by all this.”

After Mr. Floyd left for Minneapolis, Mr. Ngwolo said, he kept in touch with his friends in Houston and encouraged them to do their best and keep the faith.

“The person I met was somebody who was on their journey toward growing in their faith in Christ and, more importantly, impacting the people he was near and dear to,” said Mr. Ngwolo. “We’ve got text messages of him even while he was in Minnesota encouraging people, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing.’”

One message stuck with Mr. Ngwolo: “There was one text message in particular that said, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing, I’m going to be back in June.’ Tragically, he didn’t make it to June. But we’re thankful for his life.”

It could be said that he did return to Houston, albeit not in the way that anybody would have wanted. A public visitation for George Floyd will be held Monday at the Fountains of Praise in Houston. A private funeral is scheduled for Tuesday.

An earlier version of this article said that George Floyd was convicted in 2007 for the aggravated robbery of a pregnant black woman. Court documents show that the woman, Aracely Henriquez, was at home with a one-year-old girl, but do not say whether she was black or pregnant. The article has been updated to reflect this.

• This story is based in part on wire service reports.

• Valerie Richardson can be reached at vrichardson@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.